The most natural looking scenery in our modern landscape sometimes hides forgotten relics from Britain’s industrial past, and in one corner of the farm a copse of trees shows tell-tale signs of human activity: A large soft-sided pit about three metres deep with an unnaturally straight edge – an old chalk digging site. Embedded in one of its banks is a small brick archway that looks like the opening of a very large pizza oven! This is a nineteenth-century lime kiln, one of two found at Wild Ken Hill.

A photo of a kiln entrance prior to restoration.

Buried in hillsides, tucked away in narrow valleys or hewn out of coastal cliffs, lime kilns can be found across the UK. The Norfolk Heritage Explorer lists twenty recorded lime kiln sites, and other counties have more than three hundred. The majority are disused structures whose use has passed out of living memory and are being slowly returned to nature by erosion and decay. This was the destiny of the kilns at Wild Ken Hill until a series of pre-pandemic bat surveys revealed a very important reason to keep them intact: The southern kiln is one of the county’s two known winter roost sites for Brandt’s/Whiskered Bats, two species belonging to a group known as ‘small Myotis’ which also includes Alcathoe Bats.

In this blog post, we’ll explain why there are lime kilns at Wild Ken Hill and what we’ve done to protect these valuable underground habitats.

We champion the power of healthy soil, but to understand why lime kilns are found here we need to look at what lies beneath this shallow fertile layer.

The serene rolling countryside of West Norfolk sits on top of some surprisingly complicated geology. A hodgepodge of deposits left behind by retreating glaciers – silt, sand and gravel, which fill in and smooth over crimps and folds in the much older chalk bedrock beneath.

A geological map of the land at Wild Ken Hill, showing an assortment of silts, gravels, clays, chalk and sandstone. Image source: BGS Geology Viewer

This bedrock formed when a big slice of England was under the warm sea of the Cretaceous period 70 to 100 million years ago.

The particular wiggles found beneath both lime kilns are the cheerfully named West Melbury Marly Chalk and Zig Zag Chalk formations. They’re divided by a ribbon of sandstone and overlaid with pockets of glacial silt, sand and gravel known as ‘superficial deposits’.

The ‘geodiversity’ of the area is the reason Wild Ken Hill is home to such a wide variety of habitats and species. The underlying geology determines the chemical composition of the soil, which in turn affects the plant species that can grow there. In just a short walk across the project, it’s possible to cross up to nine geological formations and deposits!

When limestones like chalk are subjected to high temperatures and mixed with water, they produce ‘slaked lime’. This useful substance has coated buildings for millennia and been mixed with sand and dust to form mortars and concretes since early Roman times.

In rural East Anglia lime was an important part of the local economy. It was quarried, burned and spread on fields to increase crop yields. Today commercially produced lime is used to boost grass growth on dairy farms and improve soil pH on cropland.

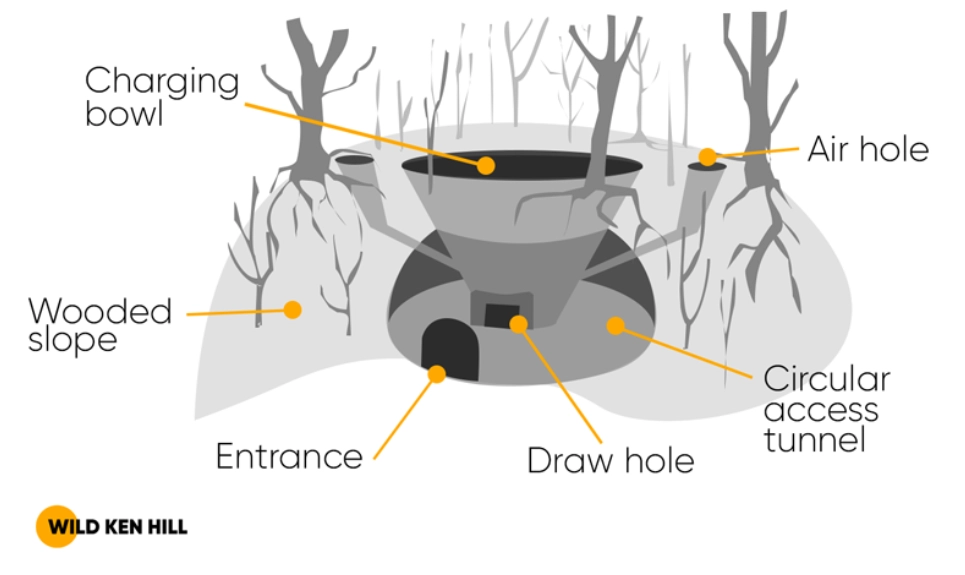

Early kilns were simply layers of firewood and limestone stacked together in a mound covered with clay or turf, and slowly burned. More sophisticated kilns built out of stone or brick came in two designs:

When a kiln reached temperatures of over 800 degrees Celsius, the limestone would separate into its component parts: Solid lumps of calcium oxide – lime – which would drop to the bottom of the kiln ready to be collected, and carbon dioxide which would escape into the atmosphere as a gas.

Experts estimate these lime kilns, both draw kilns, were built in the 1800s and possibly in use as recently as the 1930s as the central charging bowl and air holes are edged in modern brick.

An illustration showing the different parts of one of the lime kilns at Wild Ken Hill.

But more than a century of exposure to water and frost has taken its toll. With each cold snap, moisture within the walls freezes and expands, slowly opening cracks in the bricks and mortar before melting away, leaving the kiln walls weakened. By 2024 the interior chamber of the southern kiln was struggling to support the huge weight of the earth bank above it and was at risk of collapse.

Already, brickwork surrounding one of the three draw holes had slumped to the ground:

A partially collapsed draw hole.

The southern kiln has been known to be a winter roost site for bats since at least the 1980s. Ash Murray, bat expert and West Norfolk Reserves Manager for the Norfolk Wildlife Trust, writes:

“To hibernate and conserve energy over winter, all species of British bat require undisturbed sites with relatively constant cool temperatures and high relative humidity levels like caves or artificial structures with similar characteristics, such as lime kilns, cellars, ice-houses and tunnels.”

So with few natural underground features in Norfolk, old man-made structures like the lime kilns act as important habitats.

If you’re wondering why we’ve been writing “Brandt’s/Whiskered” so far, it’s because these species within the small Myotis group are so similar that correct identification would mean capturing and handling the tiny mammal, whose body is no longer than a thumb. Disturbing bats during hibernation can harm their chances of survival, so it’s not possible to accurately identify to which species – Whiskered, or Brandt’s – the bats belong.

Whiskered/Brand’s Bat. Image source: Bat Conservation Trust

In addition to Whiskered/Brandt’s Bats, the lime kiln is also regularly used as a winter hibernation site by Natterer’s Bats, Daubenton’s Bats, Brown Long-eared Bats and Pipistrelle Bats.

Bats are key ‘indicator species’, whose presence or absence tells us about the health of a particular ecosystem, and with this much bat activity at the southern kiln it’s no wonder protecting them was a high priority for the conservation team!

A Race Against the Elements

Conservation Manager Hetty looks down into a jungle of Hart’s Tongue Fern growing from of the walls of the charging bowl.

Until this summer, efforts to protect the most vulnerable kiln focussed on covering the charging bowl to reduce the amount of rainwater saturating the brickwork and seeping through to the interior walls of the structure. Activity at the site had to be carefully timed to avoid hibernation season.

With a temporary protective tarpaulin in place, the conservation team spent winter 2024/25 planning for the kilns’ long-term restoration with the help of specialist contractors.

Working quickly over summer, a large amount of earth was scraped back to unearth brick steps and the original floor of the circular access tunnel. A sturdy door was installed at each kiln with a metal grille to make sure bats can fly in and out, and the occasional bat brick was added to provide extra roosting options.

By August both kilns were fully excavated and restored revealing the fascinating detail of their original construction:

Left: The original carrstone and clunch entrance supported by a new brick arch. Centre: A bat brick in a repointed draw hole. Right: A view of the vaulted ceiling and new door into the circular chamber.

Thank you for reading, we’re delighted that two of the last remaining underground bat hibernation sites in Norfolk have been secured for the future. Perhaps for another two centuries!