For the last twenty years I have worked for nature conservation charities setting up and implementing bespoke monitoring strategies that gauge change over time and inform the management of nature reserves. In the last ten years, I have done the same for rewilding projects too. I am also a natural history nut, being a founding member of the pan-species listing community where we try to see as many species as we can in the UK in our life time (at the time of writing I’m on 7452 species). I went part time in 2019 to expand my freelance ecological consultancy work and at exactly this time, I was contacted by the Ken Hill Estate, first visiting the site in March. Within a month I had designed a monitoring strategy for the site and I was on the ground by April. It’s now nearly October and the baseline surveys are almost all complete.

The methodologies need to be standardised and scientifically rigorous. The bird survey is based on the Breeding Bird Survey transect methodology while the mapping uses the National Vegetation Classification system. The vegetation structure survey and invertebrate surveys follow methodologies that I have carried out on a number of rewilding projects, meaning there is an ever-growing data set of which to compare the Ken Hill data too. I am also keeping an annotated species list for the Estate based on my findings and everything else that’s already known from the site.

The varying soils types mean the site is extremely rich overall, with pockets of high quality and wider areas that are less rich, leaving plenty of room for improvement with the rewilding approach. That said, the invertebrate assemblage is already very rich with nearly 750 species recorded so far.

It no longer makes sense to us to grow crops here. We do not want to follow the harsh modern agricultural techniques required to make a profit any more. Nor do we fancy being so reliant on the farming subsidies we receive from the EU.

It no longer makes sense to us to grow crops here. We do not want to follow the harsh modern agricultural techniques required to make a profit any more. Nor do we fancy being so reliant on the farming subsidies we receive from the EU.

We will let the soils recover, the natural vegetation grow, biodiversity explode once more – we will let nature return

Instead, we will let this land go wild. We will let the soils recover, the natural vegetation grow, biodiversity explode once more – we will let nature return. Other projects around the UK – in particular Knepp in Sussex – have demonstrated the astonishing impact of this approach in improving biodiversity, and providing natural climate solutions like carbon capture and flood defence.

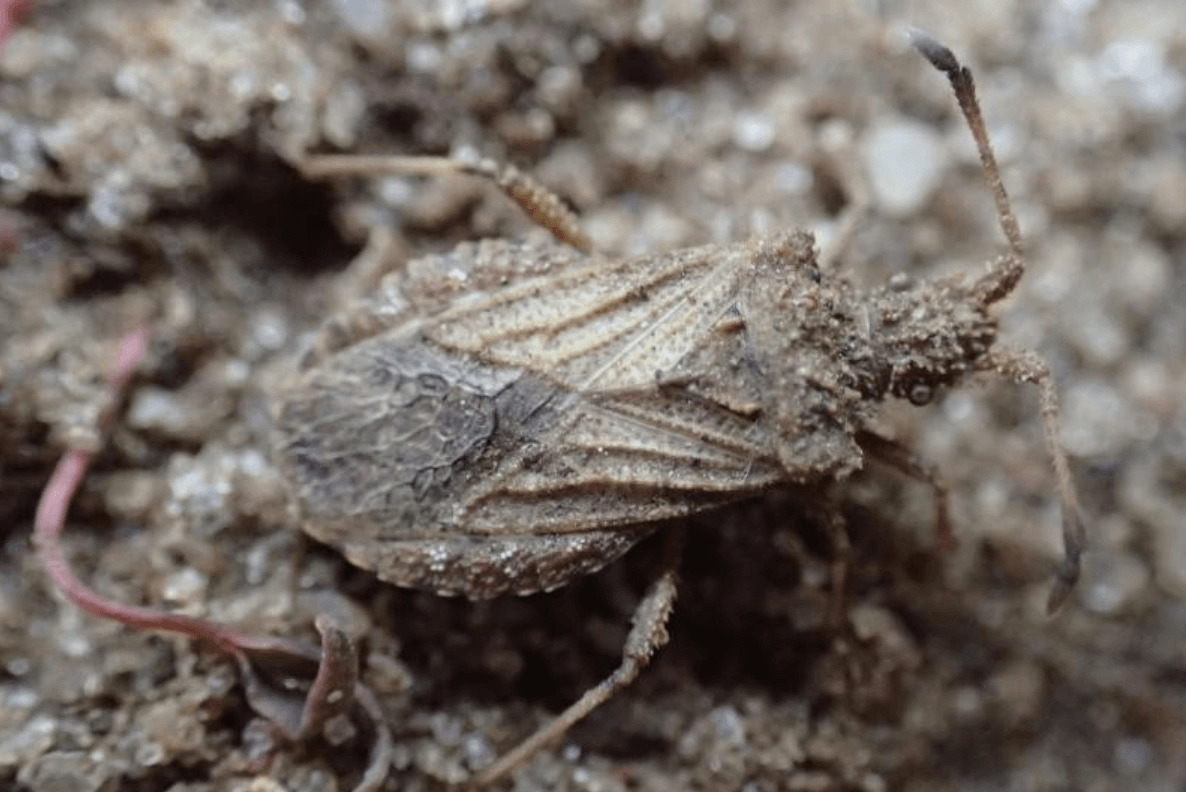

Highlights include the Breckland Leatherbug Arenocoris waltlii, listed as Critically Rare, this species of bug’s stronghold is the Brecks and in this survey, it was found in two fields that are extremely Breck-like. Some nice deadwood invertebrates were found too, such as the parasitic-wasp mimic cranefly Ctenophora pectinicornis. This nationally scarce species lives in dead and decaying wood as a larva and with so many veteran trees dotted around the site, it’s not surprising the site is good for deadwood invertebrates. The biggest tree I measured is an oak of girth at breast height of well over 6.5 metres.

The Plantlife Index for arable plants is over 110, the highest I have ever recorded anywhere, making the rewilding area of the Estate alone internationally significant for arable plants. A sea of Corn Marigold and Stinking Chamomile (both listed as Vulnerable) might have been the visual highlight but the diminutive Annual Knawel was perhaps the rarest being listed as Endangered.

I can now spend the winter identifying specimens and writing up the reports. I am expecting we should have a species list of around 2000 from 2019 alone. It’s a fascinating project to be involved with and I couldn’t have done it without the hospitality and support of everyone on the Estate.